‘Cold blob’ of Arctic meltwater may be causing European heat waves

Baku, March 17, AZERTAC

Global warming disrupts weather in many ways, but Europe’s string of record-breaking hot and dry summers has defied an easy link to climate change. Climate models do show Europe warming faster than the rest of the planet, but the recent scorchers were triggered by peculiar weather conditions: masses of hot, dry air parked over the continent, blocking any incursions of cool or moist relief.

A new study suggests global warming could be responsible after all. It proposes a chain of events that starts with an infusion of meltwater from shrinking Arctic ice, which ultimately alters massive ocean currents and regional air circulation patterns. The study, published late last month in Weather and Climate Dynamics, also suggests monitoring such patterns, which are apparent during winter months, could allow forecasters to predict extreme summer heat months to years in advance. “Physically what the authors write makes sense,” says Judah Cohen, a weather scientist at Atmospheric and Environmental Research.

Arctic melting—from both floating sea ice and glaciers on Greenland and elsewhere—is adding roughly 6000 cubic kilometers of water or more to the ocean per decade, more than enough to fill the Grand Canyon. As that freshwater pours into the North Atlantic Ocean, it sits on top of heavier ocean saltwater and impedes mixing. With less heat being stirred in from below, the surface water gets colder than usual during the fall and winter months, says Marilena Oltmanns, a climate scientist at the U.K. National Oceanography Centre. This phenomenon may explain the so-called “cold blob,” a patch of sea in the North Atlantic that NASA modeling suggests is one of the few spots on Earth getting colder.

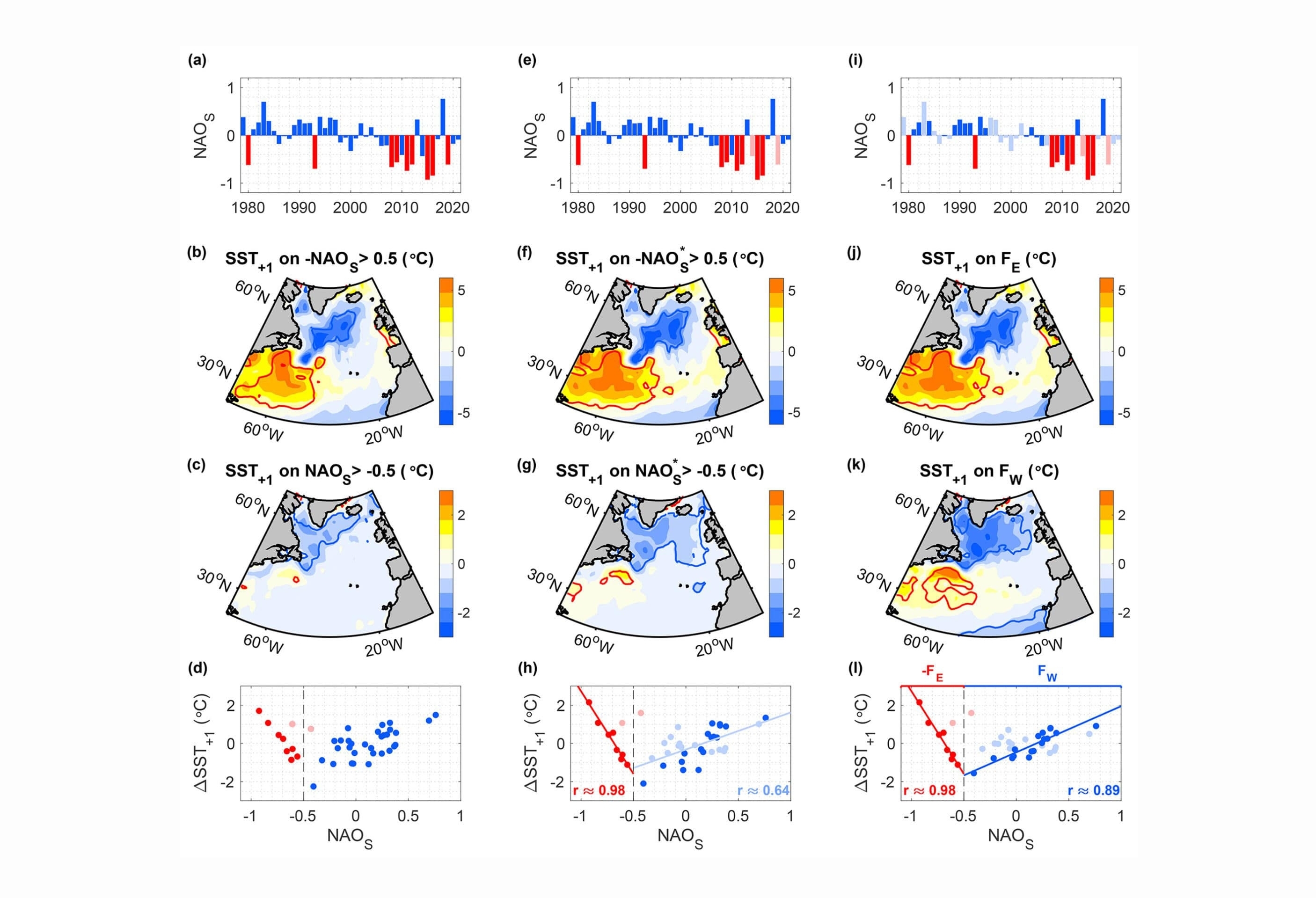

Then, after studying 4 decades of ocean and atmospheric data, the team hypothesized how the freshwater and the resulting cold blob might affect European weather. North Atlantic storms draw energy from the boundary between the blob and warm waters farther south, Oltmanns says. When the freshwater-induced cold blobs were more intense, the boundary was sharper, the data showed. The result was stormier winters with more powerful westerly winds.

Because of the Coriolis effect, a phenomenon linked to Earth’s rotation, winds can sweep water laterally. As a result, the stronger westerlies move a warm ocean flow called the North Atlantic Current—an extension of the Gulf Stream—northward from roughly 45°N to 60°N. That shift can persist into subsequent summers. And like a barrier, this warm current, curling up and around the British Isles, deflects the jet stream, allowing a mass of hot, dry air, sometimes called a high-pressure blocking system, to camp out over Europe.

That’s a complex mechanism, but Oltmanns says the statistics back it up. For example, the team analyzed the 10 hottest and 10 coldest summers in Europe since 1980 and the North Atlantic conditions that preceded them. The hottest summers were all preceded by big freshwater events, whereas the coldest ones weren’t, Oltmanns says.

“The study convincingly puts meat on the bones of an expectation I and others have had for a while—that the cold blob south of Greenland would influence North Atlantic weather patterns, as well as those downstream over Europe,” says Jennifer Francis, a climate scientist at Woodwell Climate Research Center.

The scenario could complicate another theory about Arctic meltwater: that it could be slowing the Gulf Stream by reducing the amount of salty water that sinks in the North Atlantic and helps drive the current. In theory, a slowing Gulf Stream would deprive Europe of heat and could unleash more extreme weather including deadly cold spells, as dramatized in The Day After Tomorrow, a 2004 climate disaster film. But if the researchers are right, the melting Arctic might make Europe warmer, not colder, Francis says, conclusions that “generally fly in the face of expectations for a more Day After Tomorrow-like scenario.”

Oltmanns suggests the study’s methods could aid weather forecasters and public health officials during the winter so they could prepare for summer heat. “If we had known the mechanism before,” she says, “we could have been able to predict these summers in advance.”

At least 20 killed, 21 injured in Pakistan-China highway bus accident

More than 2,000 people arrested nationwide in pro-Palestinian campus protests

Island nation of Sao Tome and Principe to ask Portugal for colonial reparations

Abu Dhabi's ADNOC says oil production capacity reaches 4.85 million bpd

China launches Chang’e-6 mission to collect first samples from the moon’s far side